What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

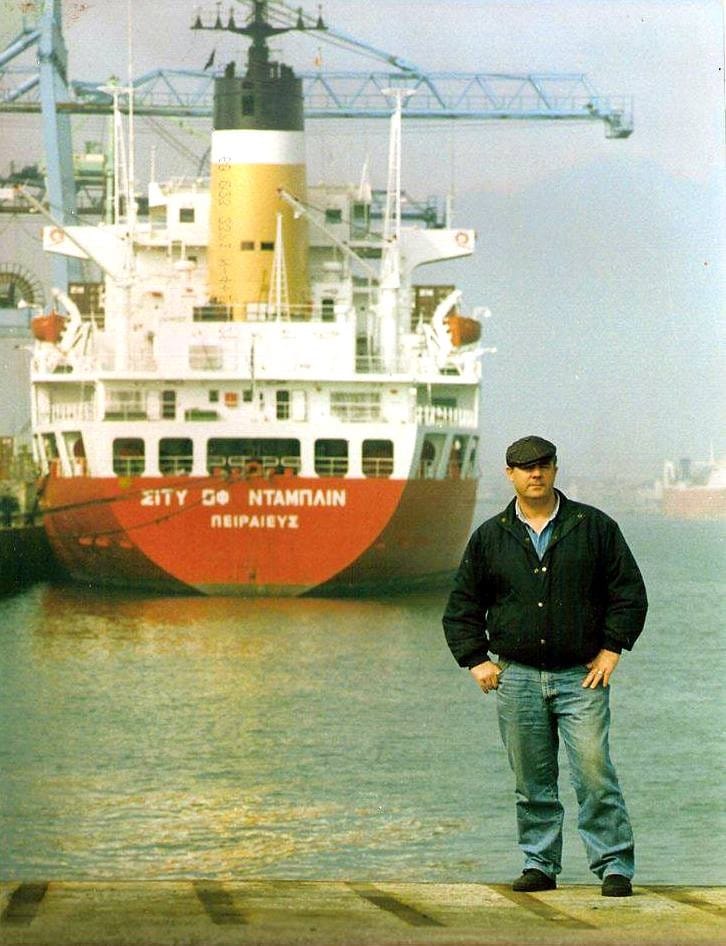

Members of the Dublin Dock Workers Preservation Society have gathered thousands of photos, documents and artefacts, which need a home.

Paddy Cunningham, standing six-foot four, could handle the bulls. But most dockers, says Jimmy Carthy, would dodge the livestock for fear of a whack.

Carthy started at Dublin’s docks in 1963 and retired in 2003, but he and his fellow ex-dockers haven’t abandoned the area.

Members of the Dublin Dock Workers Preservation Society, they have gathered thousands of photos, documents and artefacts, and they’re hoping for a more permanent place to display these, ideally somewhere near Dublin’s docks.

So far, they’ve struggled to find the collection a home.

When Carthy bumped into Declan Byrne in a Chinese restaurant in Coolock in 2011, he wasn’t sure what to say other than, “Hello.”

The pair had worked together down the docks but hadn’t spoken since Carthy’s retirement. Once they got down to reminiscing, the memories poured out.

Carthy drove the four-wheel bogies down at the docks, trolleys that carried goods off the ships. It was then onto the livestock unloading – and once, only once, it was coal shoveling.

“I’d holes in me hands, and I said, ‘Never again,’” he says. “Anyway, from seeing Declan that day he got in touch with me two, three weeks later and we’d our first meeting,” he says.

Since then, Byrne has been the main driver of the archive.

When Dublin’s docking was at its height, around 3,000 men would show up daily at the docks, says Byrne. “A foreman or foremen stood there and his requirement could have been 100 men and they could have had 500 men standing in front of them looking for work.”

This was what was known as “the daily reads”. “If you worked and wanted to feed your children you’d go to a 7am read,” says Byrne. “If you weren’t picked, you’d tell your wife and go over to an 8 o’clock or 10 o’clock read.”

Byrne worked as a docker from 1972 until 2000. As mechanisation, forklifts and containers came into widespread use, the Dublin docker’s trade largely died the death.

Since the preservation society’s first meeting, Byrne and crew have been asking around for photographs and artefacts from the residents of the Docklands and the surrounding areas.

“We never know what’s coming at us,” he says. “We’ve been donated 4,000 photographs as well as documents.”

“Totally unprofessionally”, as Byrne puts it, the documents are kept in his house. The many photographs are stored at former co-worker Alan Martin’s house.

Martin was first employed as a checker, someone who literally checked the cargo coming off the ships.

“You’d have your book and you’d check stuff into the shed, make sure it matched up, and then you’d make out the punch docket for the docker,” he says. “I got promoted then and moved into the shed. You’d make sure people got the right stuff and you’d make sure the shed was secure.”

Martin worked as docker from 1963 until 2010. He estimates that around 2,000 people worked as dockers when he started.

“We went on a tour of the docks there a while back and the place was empty,” he says. “In our time, those quays would have been full. There was only two or three ships there.”

As the 1970s and ’80s rolled on, the docks cleared out, with small pockets still remaining in Ringsend and East Wall, he says.

Since 2011, Martin has worked at uploading the 4,000 or so photographs online. He, like Byrne and Carthy, would like to see something a bit more concrete though.

“Ideally we want a proper Dockland museum,” says Martin. “It’s not like we’d be unusual. They have them in Liverpool, London, Bristol, Glasgow. Anywhere there was a big port they have them.”

There once stood a factory, says Byrne, where bombs were made.

The munitions factory, which Byrne says was located near where the port centre stands today, employed women from East Wall and environs to make bombs during World War One.

Last year, the East Wall History Group and the preservation society launched their project “Did you granny make bombs for the war?” in an attempt to identify some of the women from the photographs that had been donated.

This, and other efforts, have brought the Dublin Dock Workers Preservation Society closer to the communities from Ringsend, East Wall and Sheriff Street.

Historian Pádraig Yeates threw his energy into helping Byrne and co. in 2013, the centenary of the 1913 Lockout.

Given that Dublin’s dockers were strongly linked with the strike – although, according to Yeates, many didn’t want to be – it made sense to hold an exhibition of some of the many photographs.

And given the social history of the communities living around the Docklands it’s one collection worth preserving, says Yeates. “It’s very important as a social document on the history of Dublin,” he says.

“You’re talking about two communities which are still fairly tightly knit by modern standards, in East Wall and Ringsend,” says Yeates. “The irony of it is, of course, that their industry or their trade is dead now.”

Byrne, of the preservation society, says that the Dublin Port Authority did undertake a feasibility study in 2013 of housing a permanent space for the archive.

Nothing came of this study, and now Byrne says he’s increasingly doubtful that a permanent space could be found. “We’ve put in some Trojan effort, and we thought we’d have got a lot further than we have,” he says.

As Ann Matthews, a local historian and playwright who helped Byrne connect with the communities around the North Dock, sees it, any Docklands museum would need to include the wider community.

“What they need to do, what they’re trying to do, is reach out to the thousands of people, like me, who grew up within the community and moved on to other areas,” she says. “They’re still out there and if we don’t catch them and get their stories, the story’s lost.”

Byrne had hoped that, perhaps, a portion of the community gain fund attached to the Poolbeg waste-to-energy incinerator could be put towards a more permanent space for the dock workers’ collection. But now he reckons he’s slightly outside the area covered by the fund.

Although the preservation society have had no consultation with Dublin City Council in relation to the Poolbeg Special Development Zone, the council’s arts office says it is about to lend them a hand. It’s part of the council’s National Neighbourhood Project, which is geared towards working in partnership with local communities, says City Arts Officer Ray Yeates.

“The neighbourhoods were chosen after a long period of consultation and discussion with residents,” he says. “So for over a year we’ve been talking to thousands of people in different parts of the city.”

For this strand of the project, the plan is for the National Library to work with the preservation society on a project in February, says Yeates.

This may not lead to a permanent museum, but it might strengthen the argument in the future for such a space, he says.

Jimmy Carthy hopes so. The dockers who showed him how to use a number-seven shovel for the coal shifting are long gone.

He’d like to see a dockers’ or Docklands museum soon. “The children of Sheriff Street and East Wall, they only know where the Point Depot is,” he says. “They don’t know, inside of them gates, what went on.”

Get our latest headlines in one of them, and recommendations for things to do in Dublin in the other.