Tusla says it's an offence to run an unregistered children’s home, but it places children in them anyways

So how does it square the circle?

Lots of those pet peeves you have about walking around, or hanging around, in the city’s centre? The council has a new long-term plan to tackle them.

At the top of South Great George’s Street on Tuesday lunchtime, Barry Ellis was sat on one of the colourful long benches, finishing off some lettuce from the bottom of a plastic tub.

“There’s not a lot of spaces to sit and have lunch outside,” he says. He works at a nearby hotel, and before the small space here was decked out with seats, he’d walk over to Barnardo Square near City Hall. This is closer though.

The city could soon see more of them these mini rest spots – along with a slew of other measures in the draft public-realm masterplan that aim to give Dublin’s pedestrians a bit more love and consideration than they have seen so far.

“Having pedestrians at the heart of the public realm strategy is the right way to go, to have them at the top of the pile (…). It’s very different to what’s happened in the past,” said Labour Councillor Andrew Montague, who is head of the council’s planning committee, and has seen dribs and drabs of the masterplan as it has been refined over the past months.

The reason it’s taken a while to put pedestrians front and centre – even though we’re all pedestrians at some point in our journeys – might be because there’s no unified lobby group for them, unlike for most other modes.

“There isn’t really a strong voice for the pedestrian,” said a spokesperson for Dublin City Council’s public-realm working group. “So the public-realm group and the masterplan is to (…) advocate for pedestrians in the city centre.”

The new vision for the city centre includes several moves that would start to tackle some of the regular complaints of those who live in or visit the centre:

Why isn’t there more room on pavements for pedestrians? Where’s all the public seating? Why do I have to trek around big buildings and blocks?

There’s been a public-realm strategy in place for a while, with a commitment to make Dublin a high-quality, attractive, easy-to-move-around city.

The idea of a masterplan is to lay out a more in-depth vision. “It says, ‘How can we actually deliver that on the ground?’” said a spokesperson for Dublin City Council’s public-realm working group.

At the moment, there are three areas in the city where pedestrians often feel a bit more comfortable: Henry Street, Grafton Street, and Temple Bar. Planners aim to make the areas in-between these zones more pedestrian friendly too.

That’s pedestrian friendly, not pedestrianised, said the spokesperson for the working group. “We’re looking for a greater balance between pedestrians and vehicles, so that it feels more comfortable.”

One of the geeky developments underlying the masterplan is the creation of a “space calculator” so that planners can look at complex city streets – which might have outdoor seating, trees, and bus stops, for example – and work out how much clear space there should be for pedestrians.

“The strongest issues that are coming up all the time is that it’s the pressure on pedestrian space. It’s pressure on pedestrian space not just on movement, pedestrian space is where the life of the city sort of unfolds,” she said. “It’s where you have your social activity. It’s also where the most vulnerable people move around.”

Among the recommendations is a plan for more micro-spaces – like the one at the top of South Great George’s Street.

For some time, people have been pointing to a shortage of places to sit down in the city. Those that have popped up are well used.

Look at the newish micro-park on St Anne’s Road is, at the back of Drumcondra Train Station, says Montague. “That used to be a dumping ground, or people coming out of the pub would maybe urinate in it,” he says.

It’s a different picture now, with people sitting out, a kid’s slide, too. Under the plan, the council would look to find more nooks to develop as “micro-spaces” like this.

One of the issues that came up during research for the strategy is the fact that some demographics seem to be out on the street less than others.

A survey on Dame Street found, for example, that only 0.172 percent of passers-by were children between 5 and 14 years old. (According to the 2011 census, 13.58 percent of the general population is aged 5 to 14 years.)

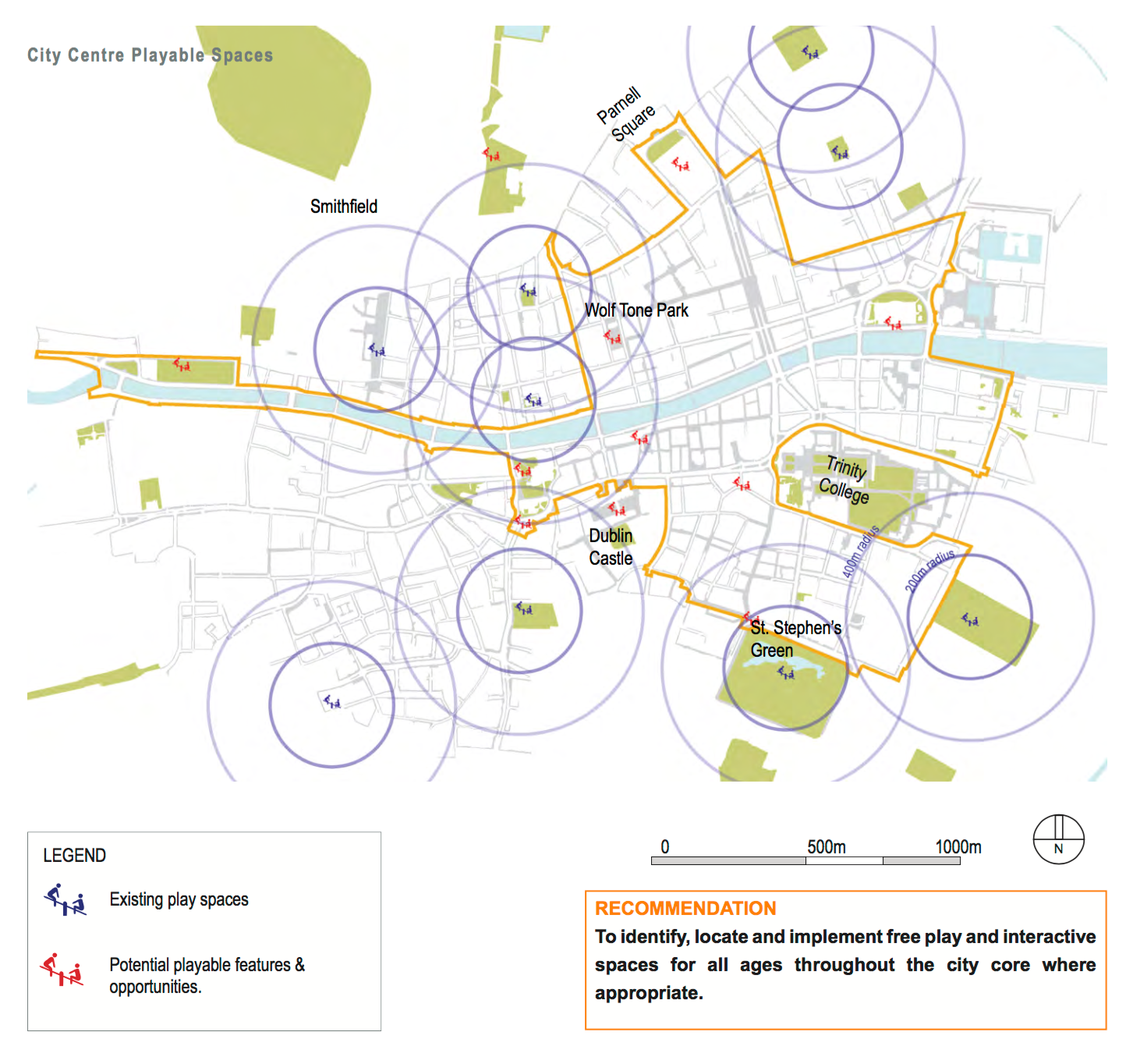

One way to make the city centre more child-friendly is with “free play” features. That can mean things such as low walls or railings, reflective surfaces, or visual and aural art works. The masterplan has 11 suggested spots for free-play features.

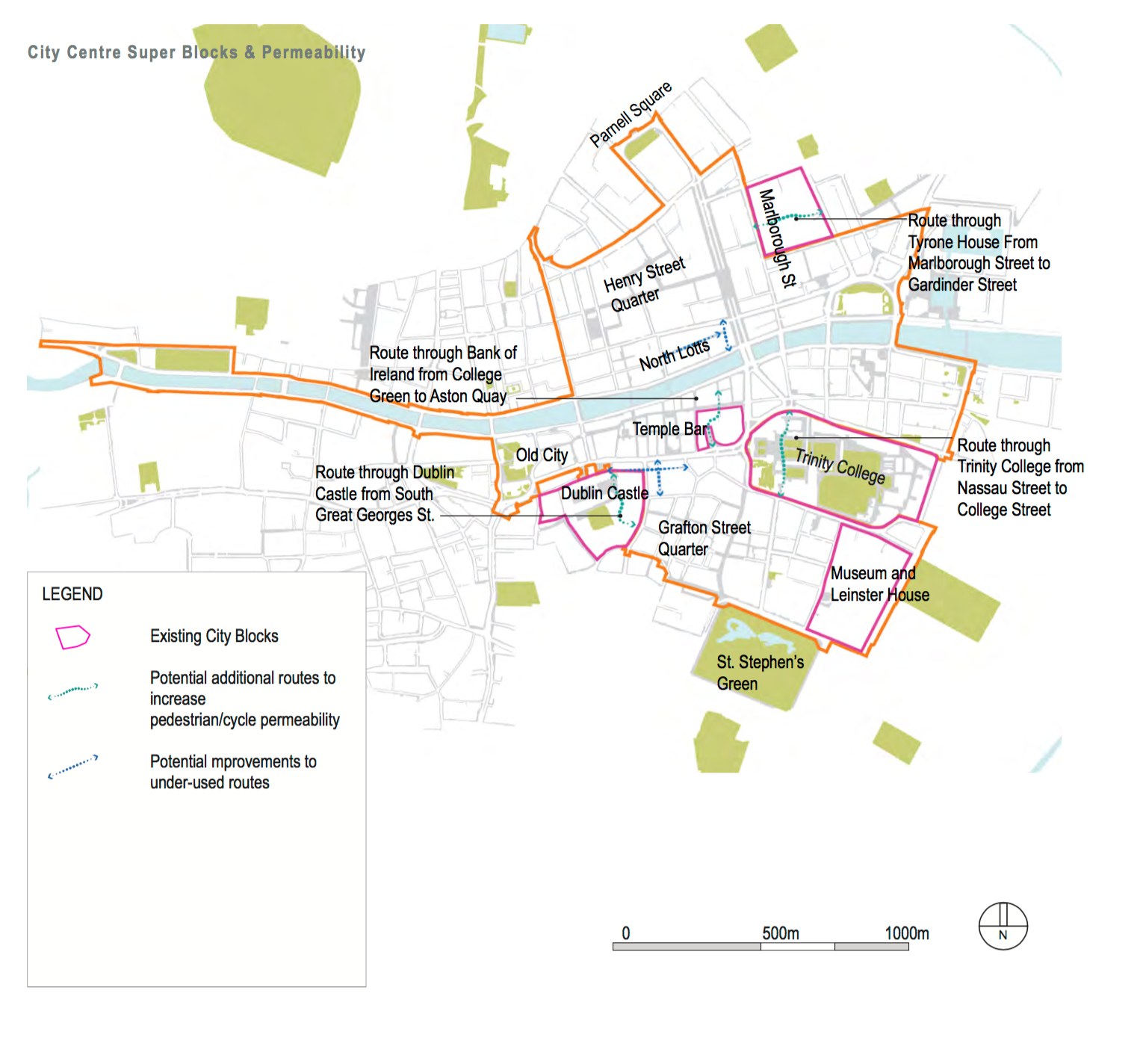

We’ve written in the past about the hassle of long walls, or impermeable blocks, which lead to tortuous routes from place to place.

“It just makes the difference between whether somebody cam walk to school, or they get in the car,” said Montague.

The classic example is bus stops: there might be one just a couple of minutes from somebody as the crow flies, but further away because of the roundabout route to take to reach it. “Then, they just do not use public transport,” he said.

The plan suggests a few extra routes, to make it quicker for cyclists and pedestrians to cut through the city: one through Trinity College, another through Dublin Castle, and one through Temple Bar. Other routes, such as North Lotts, could be made more appealing.

The funding seems to be lined up, as well. The bulk of it will come from development levies paid to the council, some of which go into a pot for public-realm-related projects, said the spokesperson from the working group.

If a particular change is part of a wider rejigging of the cityscape – like the NTA-funded College Green plan, for example – then funding might come from a different agency. “There are other projects landing in the city centre that we’ll be married with, and aligned with, that will be funded by other bodies,” the spokesperson said.

At the moment, the changes are all earmarked for the core of the city. “It’s a historic area and the area that has the most footfall as well,” said the spokesperson. “It’s us being proactive in envisaging what Dublin wants to see in its public realm, rather than reacting when projects come before us.”

Montague, of Labour, says he would like to see the ideas in the plan appear further afield, too: “A lot of the plan is only in the city centre, and I would like to see the same ideas spread around, across the city.”

He’d also like to see the footpaths upgraded. “If we had a 10-year-plan, and we graded our footpaths from 1 to 10, and the ones that are the worst get upgraded first, that’s how we should be doing it,” said Montague.

The masterplan is a long look forward, with projects planned over the coming 18 years: the aim is to finish those with the most impact by 2022, those with medium impact by 2028, and longer-term projects by 2034.

“The next step in this process is to bring forward detailed streetscape design layouts for each of the agreed projects for consideration with our partners and stakeholders,” says the report.