Nobody caught illegally dumping yet by new north inner-city CCTV

But the scheme is a success, said a council official's report, as that shows the cameras are a deterrent.

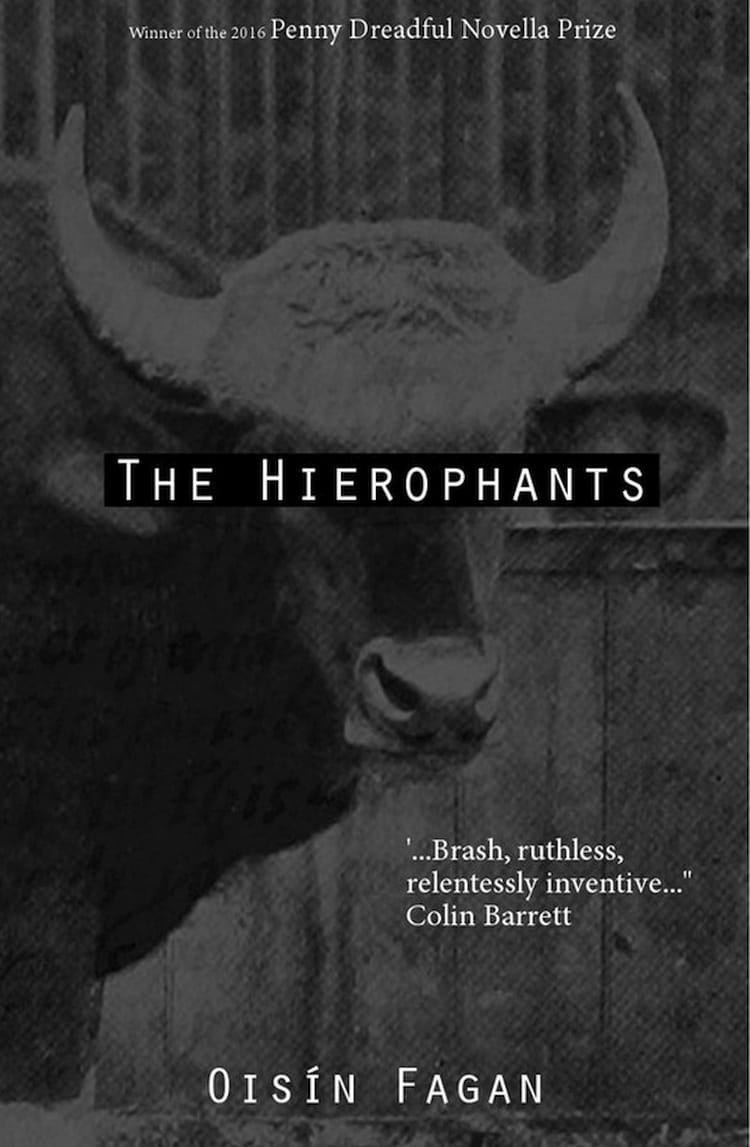

Winner of the Penny Dreadful Novella Prize in 2016, and published by Dreadful Press, this novella unfolds at a frenetic pace and is teeming with ideas.

A student stands up mid-lecture and takes the roof off Trinity College. Fire tears through the Berkeley library, claiming the lives of students and staff.

This isn’t an attack by Islamic State, or a Columbine-style school massacre, but the beginning of Oisín Fagan’s brilliantly dark and comic novella The Hierophants.

Fagan is a young writer from Meath whose stories have appeared in The Stinging Fly, New Planet Cabaret and Young Irelanders. His first collection of short stories, Hostages, is forthcoming from New Island.

The Hierophants, which he wrote back in 2011, won the inaugural Penny Dreadful Novella Prize in 2016, and is published by Dreadful Press.

Described by Rob Doyle, according to Dreadful Press, as “[f]lagrant and delirious, like a Flann O’Brien armed to the teeth and bent on vengeance”, The Hierophants unfolds at a frenetic pace and is teeming with ideas.

The novella is presented as a series of diary entries by the narrator, which grow increasingly DT’d and erratic, and are knocked into shape by a nameless editor.

The narrator – also unnamed – is a disgraced former Trinity academic, fired for turning up drunk to lectures.

Researching a new book called The Hierophants – priests who interpret arcane symbols, but the subject of the actual study remains a mystery – he’s authored two earlier books, which may accidentally have incited the bombings sweeping campuses everywhere.

The narrator is an intellectual and moral firebrand in the vein of Ignatius J. Reilly, and derides the flabby condition in which English studies finds itself. Much like the Confederacy of Dunces character, he’s older than his years and loathes everyone except his unseen girlfriend.

Feeling somewhat to blame for the bombings, he mounts an informal investigation into the affair. Probing the first student to blow up, the narrator learns of the supposedly defunct Joyce Nihilum Society, whose members carry out extreme close-readings of texts.

Like a more literary and moody Opus Dei from The Da Vinci Code, this underground society wants to achieve “deep communion with the classic texts” and “a spiritual, bloody binding with the written word”.

The narrator befriends Professor Kaz, an Austrian academic far older than himself, after the professor’s partner Dr Costello dies in the first explosion.

Kaz and the narrator grow closer through a shared love of Joyce and Erigena, and a hatred of Henry James: “Myself and Kaz share a mutual disdain for that charlatan Henry James! A male soul mate at last. This must be what the GAA encourages.”

There is a funny, twisted sequence when the narrator visits a first folio of Shakespeare’s plays in the Trinity library, only to find the society’s members have come and gone already, leaving the bard in a mound of sticky tatters.

His mind unseated at seeing Shakespeare’s folio defaced, the narrator suffers a mental breakdown, and goes on a two-week bender.

While he is in this drunken state, a female student who should be blown up rematerializes to seduce him, and hints towards the group’s plans. The narrator then resolves to track down the radicalised student cell and try to address their fatal misreading of his work.

Fagan mentioned in an interview with the Irish Times how “weak western, secular, artistic and intellectual culture is; how it couldn’t actually inspire people to change society structurally”, and that The Hierophants jokingly asks what if that weren’t the case.

The bombings trigger a clamp-down on public readings, and Kaz, who flouts this to read Joyce’s “The Dead” aloud, becomes a cause célèbre. It’s encouraging to see literary theory suddenly become a topic of discussion, even if it is in relation to the loss of human life.

When the narrator emerges from his apartment, he is made to field questions from the different news channels assembled at his door:

One prominent reporter from the BBC asked me if, as the author of Reading Is Life, I felt in anyway responsible for the recent atrocities. I said I could offer no comment and that dogs are not responsible for their fleas, Barthes’ “Death of the Author” unfortunately having disqualified me from any control over the public’s reading of my works …

“You are a formalist, then?” a reporter from TV3 shouted from the back of the crowd.

“I am not a formalist,” I said. “I am an aesthete.”

The violence engulfs English departments everywhere: mass suicides in two Scottish universities are carried out with Riverside Chaucers, and in Dante Alighieri’s birthplace students are enveloped in a ring of fire. North America is spared:

Obviously, throughout the week’s carnage, the U.S. has been left unaffected by this violence because they don’t really understand European literary criticism in any case … But in most developed nations there have been horrific literary incidents too numerous to name, and I will not do so here.

The narration in The Hierophants parodies the over-inflated and pompous style of academics.

This makes the writing strangely immune to criticism. The narrator’s notes are overwrought, flowery and pretentious, but it’s done knowingly by Fagan, even if the narrator himself is unaware.

The diary structure also allows for fun at the narrator’s expense, given his ability to write lucid prose even while drunk, and his total disinterest in re-reading his notes.

That isn’t to say Fagan’s writing is in any way deficient: The Hierophants boasts many finely wrought sentences, clever literary japes, and a breadth of literary references that will make most readers shudder.

At 75 pages, it’s hard to imagine where else Fagan could have taken the novella. Starting with a simple Bart Simpson-like premise of blowing up the school, he has developed an ambitious and complex work, with moments of great invention and humour.

It would be hard to flesh out this novella any further. It doesn’t really form the bones of a longer work like a novel, something Fagan has admitted in interviews.

Some similes could do with tightening up, and several sentences feel a little over-egged, which is understandable given the style it satirises. But Fagan was just 20 when he wrote The Hierophants, and it is an impressive literary achievement from someone of any age.

The Hierophants by Oisín Fagan (Dreadful Press, 2016)