What’s the best way to tell area residents about plans for a new asylum shelter nearby?

The government should tell communities directly about plans for new asylum shelters, some activists and politicians say.

Walled or fenced “super blocks” like Trinity College, Dublin Castle and Leinster House are obstacles to pedestrians and cyclists trying to get around the city.

All maps tell little fibs – usually to make them easier to read. Like the wayfinding maps you see around Dublin. Each has a red circle that represents the distance you can walk in 10 minutes from the “You are here” marker.

The problem is that we can’t fly, and the design of Dublin’s street network limits how far we can walk in 10 minutes.

A good example of this is the wayfinding map on George’s Quay, outside of the Tara Street Dart station.

It suggests that you can reach the front door of the National Gallery of Ireland from Tara Street in under 10 minutes. As the crow flies, the gallery is about 625 meters from Tara Street.

But this doesn’t take into account the massive detour you have to take around Trinity College. The true distance is just over one kilometre.

Walking around the east side of Trinity gets you to the gallery in 13 minutes. If you walked around the west side of Trinity, Google Maps suggests that you would reach the gallery in 14 minutes.

Trinity is a very big impermeable block right in the middle of Dublin’s city centre. Diverting traffic around such a big block creates all sorts of problems for planners and road users.

Jane Jacobs, a hero among urban planners, advocates for smaller blocks in cities. In fact, Jacobs dedicated an entire chapter of her classic book The Death and Life of Great American Cities to the matter.

She argues that small blocks are crucial to cities’ economies. They create a greater supply of feasible spots for commerce, as more places can be reached in a short walk. More route choice means it’s more possible for strangers to happen upon your shop.

But it’s not all about money. “Sometimes it’s just nice to take a different route home than you took to work,” says landscape architect Daibhí Mac Domhnaill. Mac Domhnaill thinks smaller blocks are desirable, not only because they shorten journey times, but because they open up different route possibilities to explore.

“Trinity is an interesting one,” says Mac Domhnaill. “The front of Trinity onto College Green is one of the greatest landmarks and meeting places in the city. But a lot of the other facades of Trinity are very poor, there’s very little interaction – a lack of street-level activity.”

Mac Domhnall is hopeful that connections between Trinity and the outside world could be forged, saying that he thinks the Science Gallery development on Lombard Street has had a hugely beneficial impact. “I think there’s huge scope [for more connections], but it has to be delivered through a partnership.”

The Design Manual for Urban Roads and Streets (DMURS), serves as a guide for Irish planners and engineers. It says the optimal block size for pedestrian movement is 60 meters by 80 meters. It acknowledges that some must be bigger to accommodate things like civic buildings, but says there should be ways for pedestrians to cut through these larger blocks.

The government is good at giving advice, but not as good at taking it. Leinster House occupies a huge amount of real estate in central Dublin and is impenetrable to pedestrians and cyclists. If you are on Kildare Street and want to move east, your options are Nassau Street or St Stephen’s Green, which are about 380 meters apart.

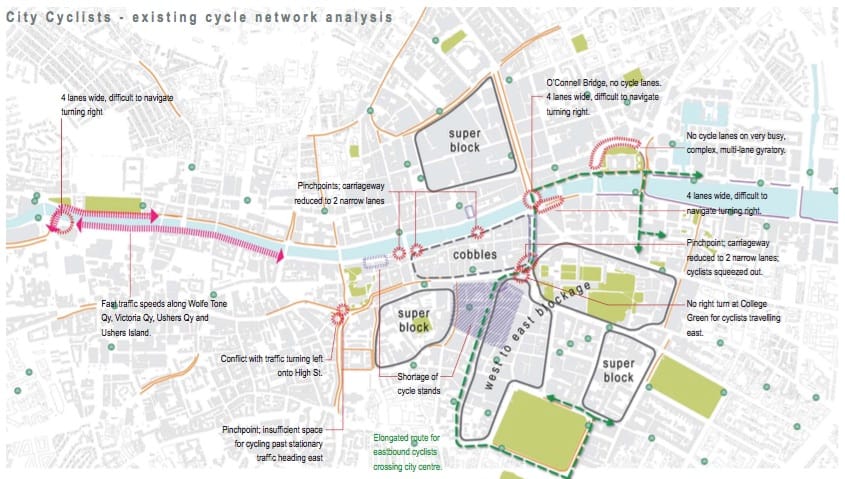

Back in May, Dublin City Council Executive Landscape Architect Peter Leonard, gave a presentation to the council’s Cycling and Walking Committee on the progress of the Public-Realm Masterplan. The Public-Realm Unit created a map analysing the existing cycle network.

“If you have a city core like Dublin, where you do have these super blocks – like Dublin Castle and Trinity College,” Leonard explained in a recent interview, “it basically corrals people into a more limited network of streets. What happens then is that you have much more pressure on some of the main connecting arteries, like Dame Street, George’s Street, and Westmoreland Street.”

When all users are funnelled onto the same few streets, there is serious competition for road space. Opening up routes through impermeable blocks like Dublin Castle and Trinity may be one way to relieve pedestrian and cyclist congestion on certain routes.

Leonard says improving permeability is an aim of the coming Public Realm Masterplan. “Where there are these super blocks, if there is an opportunity to open up a new route, we will suggest that it be done.” But Leonard adds, “I suppose the challenge is, you’re going to be working with a partner to achieve that.”

As an example, Leonard takes Dublin Castle. If Dublin City Council wants to open a new pedestrian route through it, they will have to coordinate their efforts with the Office of Public Works. “Our objectives may not always align with their objectives.”

In the case of Trinity, Leonard says he understands why it needs to keep control of access to its internal spaces, for events like ceremonies. But “you could have some sort of an arrangement for a more legible route [through Trinity] that people would be more familiar with,” he says.

Trinity College Dublin Press Officer Fiona Tyrrell, says, “When new buildings on the perimeter of the campus are being planned, opportunities for creating new access facilities are always factored in.” She points to the new gate at the Science Gallery on Pearse Street, and says there are plans for another entrance on Pearse Street as part of a new business school.

When it comes to permeability, law-abiding cyclists may have more reason to complain than pedestrians.

Since cyclists are not supposed to cross Grafton Street, they have to travel along St Stephen’s Green to the south or Trinity to the north. Eastbound movements are further complicated by the lack of a right turn at College Green to get down to Nassau Street.

“Legally, what you’re supposed to do,” says Mac Domhnall, “is go north and turn right onto Fleet Street then come back down – that’s if you are brave enough to cross four lanes of traffic on Westmoreland Street.”

In general, Mac Domhnall thinks we need to “unravel the gyratory one-way systems that have been implemented for traffic. A much finer-grade network for cyclists in the city centre is crucial.”

Leonard says the public may not see a draft of the Public-Realm Plan until the end of this year. A ton of work has gone into mapping the city centre’s public realm as it is now, he says. This has helped to create a clear vision for the future.

“Rather than public realm being led by public transport projects, what we wanted to do was create a long-term vision for the city core, describe what it is that we wanted for the city and then work back from that,” says Leonard.

In a way, they are trying to take a step ahead of transport planning. Once they finish their detailed vision of what they want the city centre to look like, then it will be time to determine what type of public transport infrastructure is needed to support that vision.

“In order to create something that’s really high quality, you have to have a clear vision of what it is you want,” he says.